Martin Evans Boyer Papers, 1910-1993 (UNCC MC00094), J. Murrey Atkins Library Special Collections at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte

There are events which happen in our lives that are so startling that we immediately feel the breath of history in the air. 2020 has already had more than its fair share- the current Black Lives Matter protests; COVID-19; the presidential impeachment trial. I can count back to 9/11; to the Challenger disaster; to July 4, 1976; to the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and John F. Kennedy. Events such as those are such radical departures from normal life that we know some part of our lives will never be the same again.

Martin Evans Boyer Papers, 1910-1993 (UNCC MC00094), J. Murrey Atkins Library Special Collections at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte

But not every event feels all that ‘historic’ at the time.

When I was about 8 years old, something happened to me that I barely recall, but my parents never forgot. Our family lived in Asheboro, but at least one Friday night each month we would drive 25 miles north to Greensboro, the Big City, to eat out and go shopping. For the shopping part my preference was the tiny peanut shop beside Wills Book Store on South Elm, or the big downtown Sears store where we saw Santa Claus and the Christmas decorations.

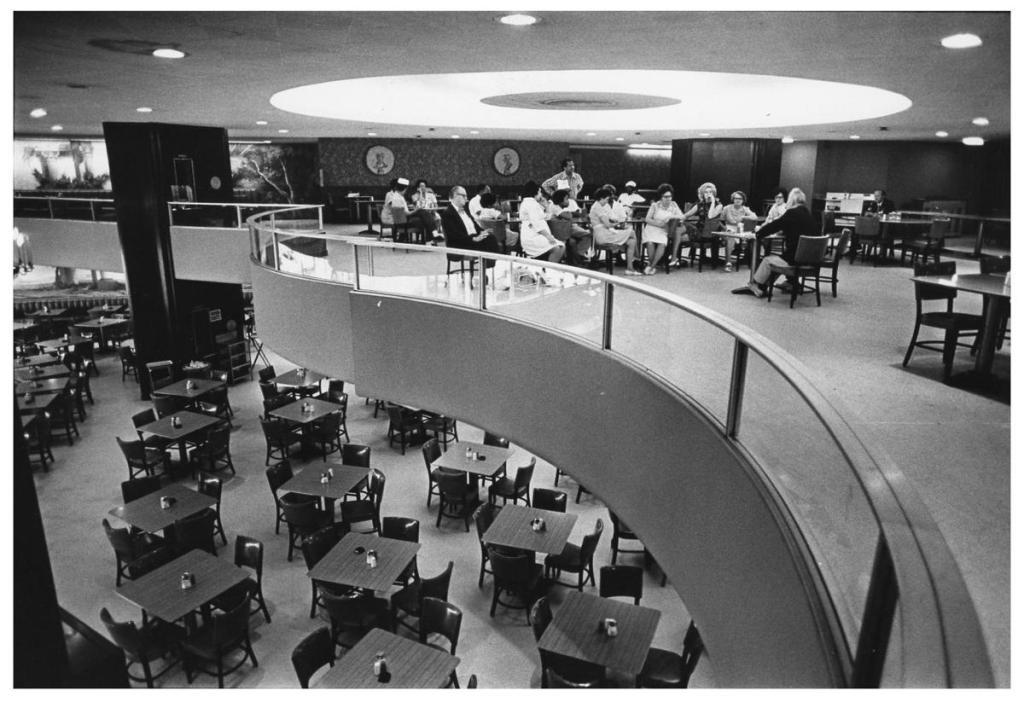

When we ate out, my preference was always the glittering palace of the S&W Cafeteria, attached to the Belk store but with its main entrance off a side street. S&W was a Charlotte chain, long gone now, except the surviving shell of the magnificent Asheville Art Deco cafeteria, now condos and lofts, like the rest of Asheville. I didn’t know all this at the time, but the Greensboro S&W, all aluminum and glass curves with shiny terrazzo floors and a broad swooping staircase up to the mezzanine, was a masterpiece of the 1930s and ‘40s style known as Art Moderne, popularized in the movies by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers and actors who always dressed in white tie and tails.

Martin Evans Boyer Papers, 1910-1993 (UNCC MC00094), J. Murrey Atkins Library Special Collections at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Barely 8 years old, for some reason I loved that place, its cafeteria line, its mezzanine, its public bathrooms intriguingly located down in the basement. There was nothing like it, not even close, in Asheboro. But my favorite thing was the revolving glass entrance door, thick as bullet-proof glass but balanced so that even I could push them like a merry-go-round, and I always made sure to be the first one through.

One Friday night in May, 1963, our family- my mother, father and younger brother- went on our jaunt to the Big City and headed to the S&W. I really remember nothing except pushing my way into the revolving door and some young man jumping into the compartment with me, walking the circle behind me, and then being grabbed by a policeman as we stepped inside. I don’t remember being scared, though my parents certainly were, trapped outside, the door held shut by the police, who wouldn’t let anyone else inside.

They told this story over and over through the years, me running ahead, ‘that black man’ jumping into the revolving door with me, them stuck outside. When I asked about it in later years, they just said it was a bunch of students, protesting, nothing to worry about.

As a historian now, I realize that I was caught in the middle of some history that night. Friday, May 17th, 1963, some five hundred protestors attempted to enter the downtown Greensboro movie theaters and the Mayfair and S&W Cafeterias. It was part of an 18-day confrontation with the Greensboro police and power structure, organized by CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, and its leader A&T football star Jesse Jackson. With the Woolworth Sit-Ins two years in the past, little progress had been made in Greensboro in integrating private businesses. As recounted in the book Civility and Civil Rights, CORE’s tactic in Greensboro was to pressure public officials and the Chamber of Commerce to open downtown businesses to black residents by filling the jails and exhausting police. Two hundred college students from A&T and Bennett Colleges had been arrested just two days before when they blocked the entrance of the S&W after being refused admission. That Friday night the manager of the S&W only unlocked the revolving doors for white customers as they walked to the entrance, so the protestor could only enter by jumping into the revolving turnstile with me. I don’t know who he was or where he came from, but he was one of more than 850 students arrested that week, so far overflowing the capacity of the city jail that they were housed in a defunct polio hospital on the outskirts of the city.

Mayor David Schenck had described Greensboro as “a city of liberal tolerance,” but after three weeks of protests he was actively considering cutting off the public water service to A&T and Bennett in order to clear out the students. Even Governor Sanford became involved, asking the heads of each school to damp down the protesters. It came to a head on June 5th when Jesse Jackson was arrested at a local church for inciting a riot, and even more protestors began to march. Mayor Schenck finally wrote to the Chamber of Commerce, “How far must city government go to protect your private business decisions? Now is the time to throw aside the shackles of past custom… Let us now more to restore to Greensboro the progressive spirit which is rightly ours.”

By June 13th, a quarter of the city’s restaurants had agreed to open to African-Americans, as well as four theaters. The changes were not as sweeping as those in Durham, or as violent as protests in Lexington. But “past custom” had been cracked open by nonviolent protests, and equality ratcheted forward another few notches. Monuments today memorialize the Greensboro Four who refused to leave the counter at Woolworth’s, and rightly so, but the thousand or so who were arrested in the protests of May and June 1963 are just footnotes to history.

That was the racist environment where I grew up in Asheboro, in North Carolina, and in the South in general. It wasn’t as overt and ugly as it was in 1860, or in 1960, but it was everywhere. I grew up in a North Carolina where black people were not allowed to eat in restaurants with white people, or use the same bathrooms, or sleep in the same hotels. That was in the air we breathed in 1960 and the water we drank, the norms that were taught us by our parents and grandparents. I don’t remember much about that night in 1963, but if I asked my mother and father why that young black man couldn’t eat in the restaurant where black men and women cooked and served the food, I’m sure they must have said, ‘that’s just the way things are.”

Things aren’t exactly that way today, but racism has been all-pervasive in the South, justifying why black people, brown people, Asian people, gay people, can be considered inferior to whites in ways large and small. Our Randolph County community was never part of the stereotypical South, our black community always less than 6% of the population, and the influence of our anti-slavery Quaker community always strong. But it was never strong enough to overcome the pervasive, systemic racism of the entire South. That’s why thousands of local Quakers moved West before the war, trying to get their families away from the stagnant, intolerant racist environment. The ones who stayed made valiant attempts to change the system from within, supporting the Underground Railroad, or the Abolition movement; voting against joining the Confederacy; refusing to serve in the rebel army; joining the Red String anti-Confederate secret society, and later joining the national Radical Republican party.

But it was still a racist environment they lived in, home to the Ku Klux Klan, the Grandfather Clause, Jim Crow, Separate but Equal and Segregation. It’s still a racist environment we live in, with Obama’s Birth Certificate, Charlottesville White Nationalists, Ferguson Missouri, the Charleston Church Massacre, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd…

We chip away at the institution of racism in many different ways. Find yours. I let a black man squeeze into the revolving door at the S&W Cafeteria, and I try to find the truth of Randolph County history. Someone else in the last week, the great-grandson of a man drafted into the Confederate Army against his will, who deserted and joined Union Army, hired the only African-American driver in NASCAR, who drove a Black Lives Matter car at Martinsville, and triggered NASCAR’s first-ever ban on Confederate flags and symbols.

Our community was never part of the stereotypical South, and it’s up to us to be more than passive participants in history. It happens all around us whether we realize it or not.

POSTSCRIPT: This was written as a letter to the editor of our local paper, the Courier-Tribune, which can trace its origins back to 1876. It was published in June, as one of the last accepted submissions from local people. By December, the last staff reporter retired, leaving the news room empty and what remained of the paper supplied by Gannett stringers. This winnowing-out of local newspapers happened over and over in 2020, making we local historians wonder what will be the source of local news in another 10, 20 or 50 years. I’m republishing this here at the end of 2020 lest it disappear forever.

The S&W chain was founded in1920 by Frank Sherrill and Fred Webber, who opened their first Cafeteria in the Ivey’s department store in Charlotte, NC. The restaurant served Southern buffet-style food at a low cost, and quickly expanded to locations all across the major cities of the South, from Washington, DC to Atlanta, GA. The Greensboro protests triggered the integration of the entire chain in June 1963.

Charlotte architect Martin E. Boyer, JR. (1893-1970) designed most of the restaurants. The Knoxville, TN and Asheville NC locations are considered Art Deco masterpieces, and both are now on the National Register of Historic Places. The post-WWII Richmond, VA, and Greensboro (built 1947) locations were similar in appearance, with swooping Art Moderne staircases and mezzanines. The Greensboro location closed in 1975 and was torn down in 1976. After being a vacant lot for longer than the restaurant existed, a parking deck is now (2020) under construction at the site.

The illustrations of the pristine, new S&W are to be found in the Martin Evans Boyer Papers, 1910-1993 (UNCC MC00094) in the library at UNC Charlotte, and now digitized by NC State. Historical photos of the sit-downs can be found at https://greensboro.com/gallery/civil-rights-era-historical-photos/collection_a08bdf22-a7f8-11e4-98a1-9f4e22e1d3cc.html#5 . The sad record of the building’s destruction can be found in the Greensboro News & Record in 1976: https://greensboro.com/gallery/news/photos-a-look-back-at-the-s-w-cafeteria-closing-and-demolition-in-downtown-greensboro/collection_6c49828a-8e83-5077-baf0-d94b88a0a93d.html#10 .