Two hundred years ago, December 25, 1821, a miller from Guilford County named Elisha Coffin bought a defunct mill site on Deep River in eastern Randolph County. His improvements would soon be known as “Coffin’s Mills on Deep River,” and by 1839, as the village of Franklinsville, but at the time it was referred to as “Schean’s old Mill Site.” This Christmas day I refer to it as “my home,” as the 20-acres I own in Franklinville include the house Elisha Coffin built about 1835, just up the hill from the mill site on Deep River.

I think it’s valuable to consider how our modern picture of “Christmas” is a construction of our post-World War II consumer society. Our Christmas and Santa Claus paraphenalia is made in Asian countries that aren’t Christian and had no clue who Santa was until they started sewing millions of Santa suits for pennies a day. Russians celebrate New Years with presents and trees, and for them Christmas (January 6th) is a religious day that Babuskas spend cleaning icons in church.

January 6th in fact was Christmas in eastern North Carolina up to the 1920s, when American culture first started its homogenization through recorded music, radio, movies and television. It survived in the Hatteras Island village of Rodanthe with the annual appearance on that date of “Old Buck,” a mythical bull who headed up the Christmas festivities, which started on “New Christmas,” the 25th of December, and lasted for the next twelve days.

Those twelve days of Christmas happened when Pope Gregory XIII ordered Catholics to observe a new calendar year starting in 1582, which added 10 days to account for the fact that the Julian calendar started by Julius Caesar in 46 BC had been gradually growing out of sync with the cycles of the moon. (The Roman calendar also invented Leap Years and the month of January, but that’s another story). Since Jewish holidays were then (and now) keyed to the lunar calendar, this discrepancy was gradually creating an untenable situation where Easter and Christmas were happening later and later each century. To forestall Easter in July and Christmas in April, the Pope decreed a new calendar.

Except in England, where Henry VIII had just rid himself of meddling Catholics priests and started his new Church of England, and he wasn’t about to let the Pope tell him what to do. So it wasn’t until 1752 that England adopted the Gregorian calendar, and since 170 years had passed they were now 11 days out of sync, so by Act of Parliament the days from September 3 through September 13, 1752 just disappeared.

To further complicate things for Genealogists, the medieval church had always considered March 25th, the Feast of the Annunciation, as the beginning of the Christian New Year. This made sense to rural farming communities, as March coincided with Spring planting season. So the dates of births, deaths and weddings in parish records up to 1752 will write, for example, “February 1, 1750,” now noted in ancestry.com and other databases as “1750/51, as we would now consider any date after January 1st to be in the year 1751, not 1750. Confusing, for sure; which is another reason why regular people resisted adopting the new dating system which tinkered with the dates of important annual events.

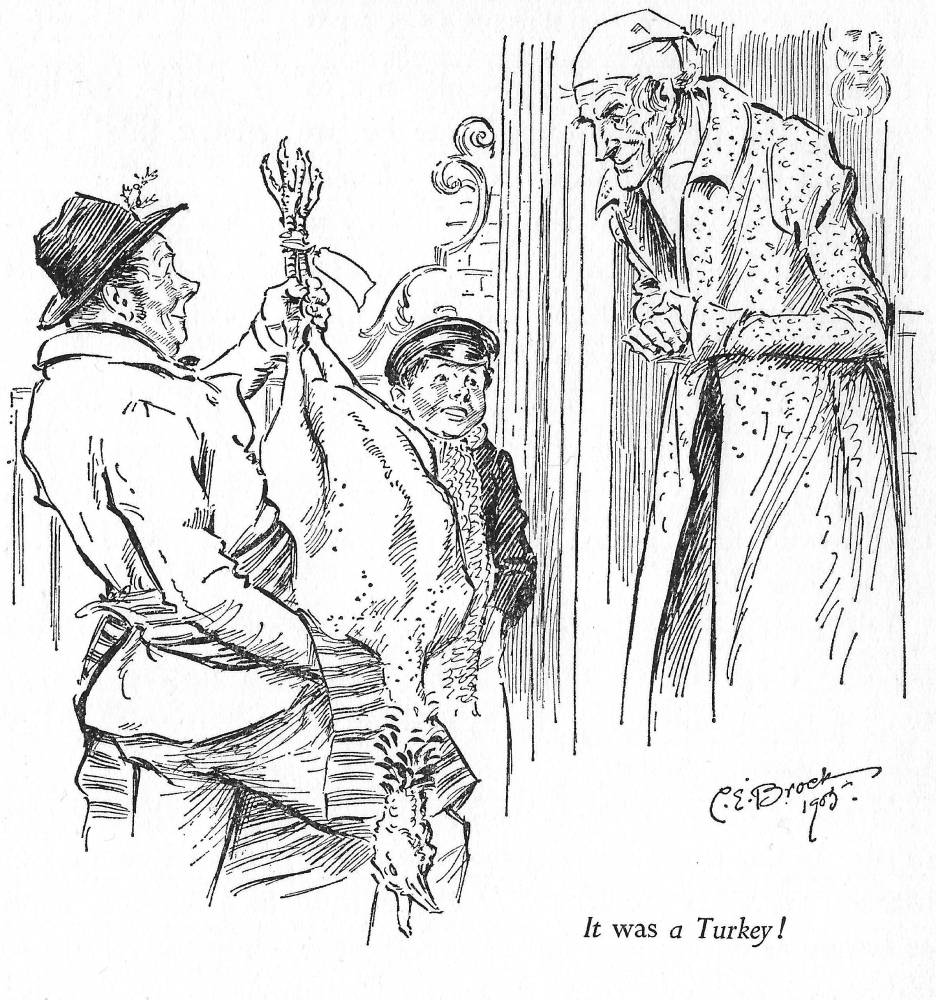

Charles Dickens, of course, is as much responsible for the apotheosis of English-speaking Christmas in world culture, through the popularity of his “A Christmas Carol.” Published in 1843, it wasn’ t concerned with the calendar changes, but in the mistreatment of the poor, and the popular festivities ignored by Ebenezer Scrooge until his transformation into a kinder, gentler man. The book begins on Christmas Eve, where we are introduced to Scrooge’s miserly attitude by his reluctance to give his employee Bob Cratchit Christmas Day off, with pay. Since that has become virtually universal and expected benefit of modern life, we don’t actually register that it wasn’t the universal custom even then. When the transformed Scrooge awakens on Christmas Day, he has no trouble sending a boy to “the Poulterer’s in the next street” to buy “the big prize turkey in the window” and having it delivered to the Cratcit family- early on Christmas morning. So Christmas 1843 was still more of a religious holiday than a work holiday.

As it was in America. Not only could Elisha Coffin get a lawyer to make a deed and have it recorded on Christmas Day, the state legislature of North Carolina, meeting on Christmas Day, 1796, created the new town of “Asheborough,” among other bills on a busy day. Here again, the busy seasons in an agricultural society were from March through October, and not even legislators and attorneys had the free time then for extracurricular activities. The “season for schooling,” also ran from October to March, and “summer vacation” didn’t end until September even up to the 1960s so children could help with the harvests.

North Carolina, and Randolph County in particular, had a questionable attitude about Christmas through their association with the Society of Friends, or Quakers. The Friends arose during a time of schism in the 17th Church of England and in the British Civil War. King Charles I married a Catholic bride against the wishes of Parliament, and tried to arrest its leaders in 1642, The Parliamentary army, or “Roundheads, under Oliver Cromwell were ultimately victorious and executed the King. A devout Puritan, Cromwell was named “Lord Protector” by Parliament, and instituted a religious dictatorship which persecuted Catholics and “Separatists,” who disagreed theologically with the Church of England. Quakers were one of these dissident sects, and were jailed, tortured and sometimes executed by the Puritans. This caused the mass emigration in the 1660s of many Quakers to the colonies of Rhode Island, Pennsylvania and North Carolina. (Ironically, with the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1662, many Puritans fled England and settled in Massachusetts and Connecticut.)

The reason for this detour into British religious history is that Puritans and Quakers alike both disliked Christmas, considering it a Papist, and even worse, a pagan festival. (Which it was, having its origins in the Roman festival of Saturnalia, which happened at the winter solstice.) In 1659 the Massachusetts Bay Colony outlawed Christmas, making it a criminal offense to publicly celebrate the holiday “by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way…” Quakers agreed, noting that there was no scriptural basis for commemorating the birth of Christ, or that it even happened in December. Increase Mather, noted Puritan minister, noted that it was only promoted as a church holiday in the 4th century AD, and that they were just trying to merge the pagan holidays into the Christian calendar to appease converts.

Christmas traditions in pre-Puritan England had gotten rather wild, with the twelve days from Christmas Eve to Old Christmas degenerating into feasting, drinking, gambling and other questionable behaviors. Even in antebellum Asheboro, as I have written previously in the entry “A Confederate Christmas in Randolph County,” people would wear masks and costumes and loudly beat pots and pans until residents fed them or gave them presents, a survival of medieval “wassailing.” Not until after the Civil War is there reliable evidence that Christmas trees were put up locally (as recounted in this blog, “Randolph County’s first Christmas Tree?”)

Our modern Christmas is our modern creation, as different from Dickens as Dickens was from Cromwell.

Even so, two hundred years ago, the man who built the house I live in today bought the land I now own. Christmas Eve 2021 is now history for all of us, as Christmas Day 2021 will be tomorrow. As Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead; it’s not even past.”

Our modern Christmas is our modern creation, as different from Dickens as Dickens was from Cromwell.

Even so, two hundred years ago, the man who built the house I live in today bought the land I now own. Christmas Eve 2021 is now history for all of us, as Christmas Day 2021 will be tomorrow. As Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead; it’s not even past.”