June 19, 1865, “Juneteenth,” was the day freedom finally came to the enslaved people of Texas, and is now celebrated as our second American independence day. But African Americans in eastern North Carolina, in counties already occupied by Federal troops, heard the news of the Emancipation Proclamation immediately, on January 1, 1863. Up into the 20th Century “Watch Night” church services were held in black communities in the place of New Year’s Eve parties, with the congregation ready to welcome freedom at the stroke of midnight. Newspaper articles show that this was actually the tradition in Asheboro. [“The following is the program prepared for the celebration of Emancipation Day to be held in Asheboro Saturday by the colored people of the town and county:” The program included “Five-minutes talks from ex-slaves.” The Randolph Bulletin, Wed. Dec. 29, 1915, page 4.]

Not much survives about Watch Night traditions here, but Juneteenth has a long and colorful cultural history out west. A hallmark of those celebrations has been the food, with barbecue, watermelon strawberry soda, red punch and Red Velvet Cake always on the table. [https://www.oprahdaily.com/life/a36479941/juneteenth-food-traditions/] While some articles said that red food symbolized the blood of the past generations of the enslaved, culinary historians now think the practice was brought to Texas by enslaved people from Nigeria, Ghana, Benin and the Congo, where Asante and Yoruba traditions included offerings of the red blood of white birds and goats to their ancestors and gods. There are stories of red trinkets and red flannel cloth being used to lure Africans onto ships bound for America, which also figure into Juneteenth traditions. [https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2018/04/inquiring-minds-uncovering-the-many-meanings-of-slave-narratives/ ]

“Red, in many West African cultures, is a symbol of strength, spirituality, life and death.” Moreover, two West African plants, hibiscus and kola nuts, were powdered and used to make red herbal teas by Caribbean and plantation communities. {See https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/what-is-juneteenth? for much more information on those food traditions.]

This reminded me of a unique episode of Randolph County history that opens up a window into the cultural life of local African Americans in colonial times. Very little information survives about individual Randolph County’s black population before 1800, but the most interesting fragment is found in an unusual place- the Narrative of Colonel David Fanning, the leader of the pro-British forces that waged a deadly guerrilla war in Randolph county in 1781 and 1782,

In May 1781 Fanning attacked a column of NC Dragoons under a Colonel Dudley, coming up the PeeDee Road from Camden, killing several men, taking prisoners and stealing their baggage train. Colonels Collier and Balfour tracked Fanning back to his headquarters at Cox’s Mill on Deep River, and “kept a constant scouting” to provide information back to the colonial forces. Several months later, Colonel Dudley with “300 men from Virginia” attacked Fanning’s fortified position at the mill, scattering the loyalist forces and taking control of Fanning’s supplies. Writes Fanning, “He took a negro man from me and sold him at public auction for 110 pounds; the said negro was sent over the mountains, and I never saw him since.” [The Narrative of Colonel David Fanning (1865), p. 17]

Fanning mentions owning a number of Negroes but this one was particularly important to him. An offhand mention in a report to General Butler, commander of the state militia, may indicate why. “Captain Henley… was in action with Fanning. Twelve surprised eighteen, killed six, and took three prisoners and a Negro, the Conjuror.” [Executive Letter Book, March 1st, 1782]

Very few enslaved people are known by name from the 18th century, but even fewer are known by a title. This title, “the Conjuror,” seems simple but provides a window into the African heritage of the enslaved in this county that has never before been opened.

In the Bible, “to conjure” means to summon or invoke a spirit or devil by magic or sorcery. The online Free Dictionary goes on to state that a conjuror, also called a witch doctor, root doctor, jujuman or obeaha, “is a priest and physician called upon by African tribal members and followers of religions such as voodoo, Santeria and macumba.” [https://www.thefreedictionary.com/conjure+man] It is based in the belief that psychic powers can be used in a way to cast spells, make enchantments, find lost items, detect thieves, tell the future, create good or bad luck, and even heal or kill.

Native conjurers were present in 1585 when the men of Sir Walter Raleigh arrived in North Carolina. Visiting the town of Secotan on the Pamlico River, the artist John White painted a dancing native he named “the flyer,” “the magician,” or “the sourcerer.” A 2008 article by George Stevenson [ https://www.ncpedia.org/conjure] cites a 1767 record from Johnston County where slaves travelled to Dobbs County to consult a conjurer named Quash, and later another in Smithfield called “Old Bristow,” to obtain powders to add to their owner’s food. The conjure was discovered when the white families became ill, and the slaves were tried and sentenced to public whippings, and to have their ears cut off at the pillory.

Most conjures do not seem to have had an evil purpose; many practitioners functioned as doctors or nurses to the enslaved community using elements of African and European folk medicine and native herbal lore. The tradition of “working the roots” was common in rural North Carolina up into the 21st century, although not commonly known to white Southerners. Like the red foods of Juneteenth, it is believed to have its origins in the folk beliefs of West Africa, home of many in the enslaved population. [https://www.ncpedia.org/root-doctors]

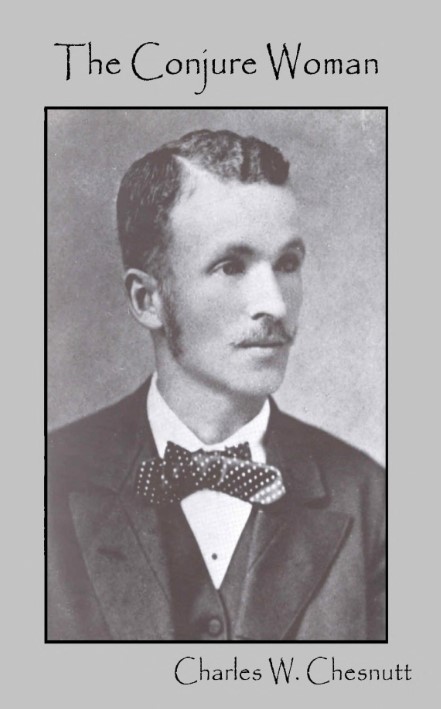

The conjure culture of Piedmont North Carolina also inspired one of the first popular works of African-American literature. Charles Waddell Chesnutt (1858-1932), a son of free people of color from Fayetteville, NC, began writing short stories in 1887. His “The Goophered Grapevine” was the first work by an African American to be published in The Atlantic Monthly. His collected stories were published in 1899 as The Conjure Woman, which was adapted at a motion picture in 1926. He contributed to The Atlantic for more than 20 years, also writing a biography of Frederick Douglas and a novel based on the Wilmington Massacre of 1898.

It’s hard to draw a full portrait of a man with no more information than his title “Conjuror;” but much of early African American culture is based on such bits and pieces of surviving facts. Without this tidbit, we would have no way of knowing that the enslaved peoples of Randolph County shared the conjure culture rooted in West Africa.